Day Three (2025-Present)

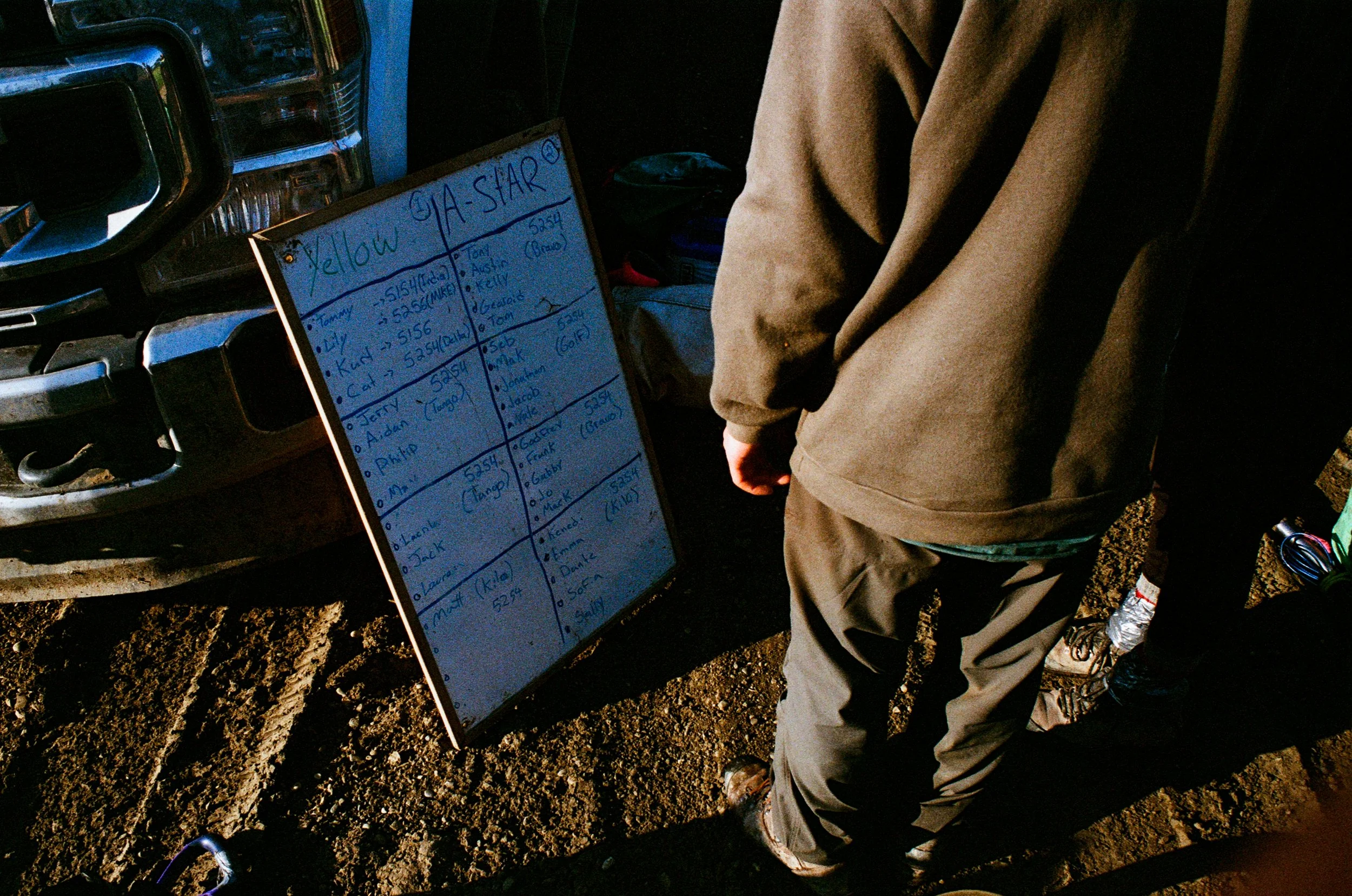

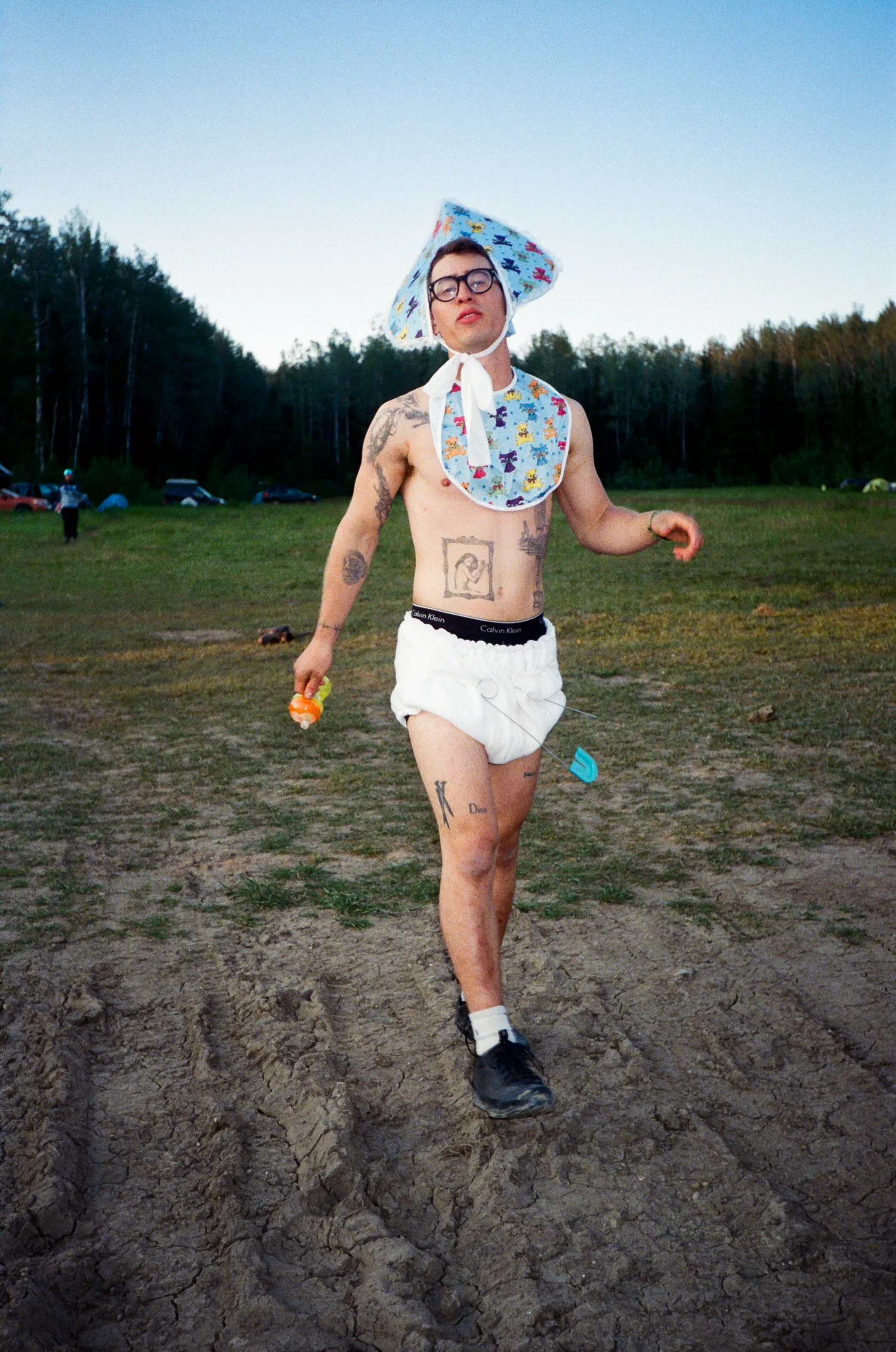

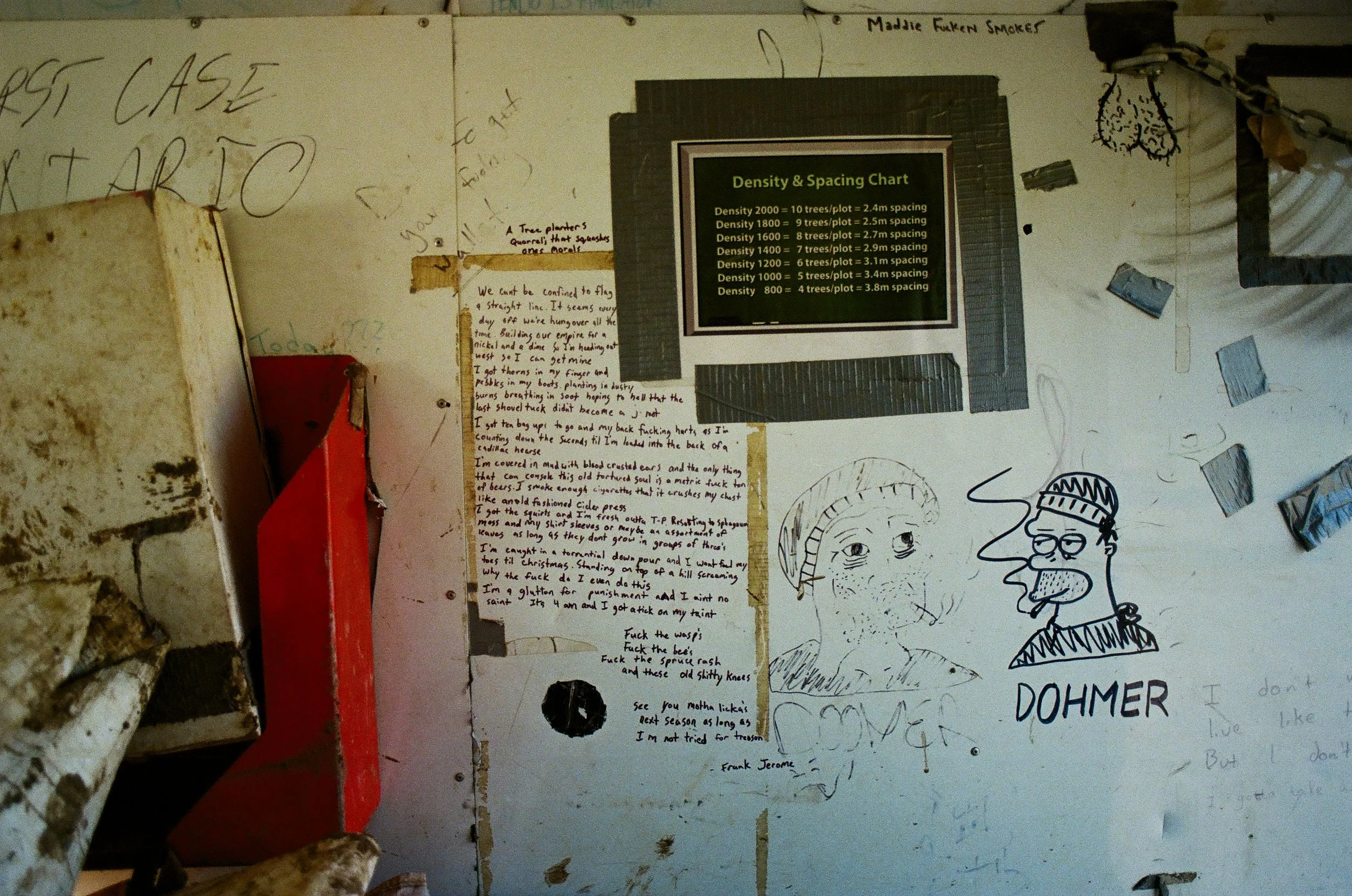

Every May, thousands of young people leave cities, classrooms, and routines to migrate to the remote forests of various Canadian provinces. Most are university students; others are seasonal workers or wanderers looking for a new experience. For two to three months, they live in temporary camps reachable only by logging roads. Their work is repetitive and back-breaking. It is both physically and mentally grueling. However, through the community and social relationships formed amongst the camp, these planters are able to endure all that they go through.

For the entirety of the contract, I lived and worked as a tree planter. During that time, I photographed the life I saw around me. This book represents the first chapter of a longer-term body of work.